How to Paint

How to Paintby Gustav Hébert

Phaideron Press, ppbk ($20)

Originally published in France in 1930, How to Paint by Gustav Hébert is a very peculiar book. It is not a “how to” by any means for its author was a trained chemist and hack photographer; not a painter. The title, one eventually discovers, is an intentional misnomer; an ironic insult hurled at the Parisian art world. Released by the reputable house of Duart Editions, the original morocco-bound volume was financed by its author and designed in the elegant style of the 19th century. It was translated from the French by Hébert himself and upon publication it caused a minor uproar. Although dismissed by most critics as frivolous and absurd, the Paris Surrealists declared it a classic. In a review published in Le Nouvel Oberservateur, André Breton hailed it as “l’amour fou illuminé.”

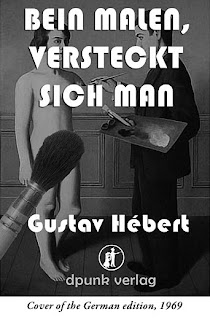

Adding to the book’s mystique was a reproduction of Réne Magritte’s painting, Attempting the Impossible (1928), which appeared on the front cover. In the absence of a subtitle this was only a cryptic clue to the nature of what was, in fact, a memoir. The title of a German edition (1967)—Bein Malen, Versteckt Sich Man (“When Painting, One Conceals Oneself”)—is closer to the mark.

Hébert, the son of a chemist, was educated to follow in his father’s footsteps, but abandoned science to pursue his true talent: chasing women. At the age of 19 he was given a camera and quickly realized the “opportunities” it afforded him. In 1921 he was hired as a photographer by the Paris-based Les Éditions d’Art Devambez, the largest publisher of lithographic post cards—those famously French risqué and pornographic relics marketed to tourists. Or, in the words of the author:

“...those pathetic souls who wandered the city like wraiths… glassy-eyed gentlemen from New York and London.”

The firm’s owner, Alfred Devambez, took a liking to the young man, and when he died three years later, Hébert found himself in charge of the lucrative enterprise. He devoted the next several years to seducing hundreds of models he photographed, amassing a small fortune, and collecting contemporary erotic paintings by artists such as Picasso and Delvaux. He became excessively concerned with the preservation of his collection and believed the paintings were fading prematurely under artificial light. He wrote to Edmund Germer (the German inventor of the fluorescent lamp) seeking advice. Several months later, Germer traveled to Paris to meet Hébert and agreed to collaborate on a series of experiments analyzing the effects of light on painted surfaces.

On November 18, 1926, they made a startling discovery. Using one of Germer’s experimental arc lamps, Hébert coated its tube with a pyotized-fluorescing powder which transformed UV into an eerie, aqua-colored radiance. By shining the lamp directly on a canvas which had been layered with a mixture of gouache and polynucleotide (a polymerase enzyme which causes pigments to erode), the light rays penetrated the opaque watercolors and—“in under a minute”—exposed the blank surface beneath.

Although Germer found the effect “amusing,” he was not particularly enthusiastic. Hébert, by contrast, was ecstatic.

“It fired my imagination—transported me to the base of Mount Helikon itself, where I stood in the shadow of the muses!”

He began referring mischievously to the discovery as “pentimento-mori” and considered using the pun as the title for his book but, eventually, ruled it out as too esoteric.

Inspired by a plan he believes will make him famous, Hébert selected twenty-six of his most explicit photographs, enlarged them to poster-size, and glued each to a stretched canvas of the same dimensions. He then enlisted the help of a painter friend whom he refers to only by the initials “M.C.” (The artist was rumored to have been Marc Chagall.)

“At my direction [M.C.] set about concealing the nudity in the pictures using the gouache mixture. With agile strokes of his brush, he clothed each model in suitably tasteful attire, using popular magazines as his guide. His génie artistique extended beyond painting over the offensive genital areas to include sartorial flourishes and embellishments such as hats, gloves, and jewelry. Working at a most feverish pace, he completed the entire series in three days!”

Hébert spared no expense framing the painted photographs, and paid the esteemed Galerie sur la lune to sponsor an exhibition. Over 2,000 embossed invitations were mailed to members of Parisian society, as well as government officials, foreign dignitaries, and stars of the cinema. Although no one had ever heard of the artist, on January 5, 1927, more than a thousand curious invitees showed up for the opening of Les habitants merveilleux de Paris: nouvelles peintures par Gustav Hébert. Since occupancy was limited to 200, many were forced to wait outside in a torrential winter rain.

Once inside, visitors were greeted by a bizarre spectacle. Standing beside each painting was a blindfolded attendant dressed in a uniform resembling a Victorian constable, i.e., a stovepipe hat, red swallow-tailed coat, white trousers, and wellington boots.

With small groups gathered before each exhibit, the lights were switched off and the gallery bathed in darkness. A whistle then blew, signaling the attendants who, one by one, turned on a small arc lamp attached to the painting’s frame.

From the sidelines Hébert observed the scene calmly:

“...I stood smoking a cigarette and watched the ensuing pandemonium. The newspapers would be clamoring for interviews. My portrait would be caricatured on the front page of Le Scat Noir. Each photograph would be described in lurid detail. The exhibition would be the talk of the town!” Finally, however, reality set in. “…my ebullience tempered by a dark cloud overhead. The authorities would be arriving soon. The festivities, alas, would reach their dénouement. I slipped out the rear exit and strolled off in the direction of home…"

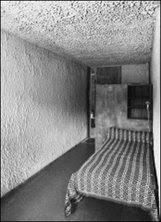

The final chapter includes a photograph of the prison cell where the author wrote his book. The accompanying ten pages describe the cramped space in such minute detail that it anticipates Robbe-Grillet and the nouveau roman.

The book concludes with this quasi-poetic description of dust-motes:

“…tiny phantoms, souls of fleas, an animated composition rising from a tethered canvas, escaping via an illuminated escalator to freedom—that pure, glittering realm of Eros—Eros everlasting. It is here (and only here) where one discovers how to paint.”

Click here to order the book from Amazon.com

For additional information on this book, see our previous posts click here and click here.